Desert Plants at Saguaro National Park Resist Ravages of Drought

By Dave DeFusco

Desert vegetation surrounding the saguaro cactus in Saguaro National Park has been remarkably stable despite the presence of extreme weather over the past 30 years, according to a progress report on an ongoing research project, Three Decades of Ecological Change: the 2020 Saguaro Census, Phases I and II, supported by Western National Parks Association (WNPA).

The research, conducted by University of Arizona master’s candidate Emily Fule and park biologists Don Swann and Adam Springer, is part of the fourth survey associated with the Saguaro Census. They found that, since 1990, the total number of perennial plants has increased in both the Tucson Mountain District (TMD) and Rincon Mountain District (RMD) of Saguaro National Park, which is located in Pima County, Arizona.

Both districts are separated geographically by the city of Tucson. The TMD, often referred to as Saguaro West, encompasses 24,818 acres of land, much of it designated as wilderness, while the RMD, or Saguaro East, contains 67,000 acres of wilderness.

The census, which takes place every 10 years, is a large-scale monitoring effort of the park’s signature plant, the majestic saguaro, whose towering bodies and upraised arms are as much a Southwestern cultural symbol as a staple of the desert landscape.

In 2020, the researchers found that the total number of individual plants, or stems, in the RMD nearly doubled to 5,056 from 2,659 in 1990, and in the TMD, the number of plants swelled to 4,394 from 2,822, or by 44 percent. Total plant cover also expanded significantly during the past three decades. In the RMD, cover extended to 15,500 square feet in 2020 from 11,300 square feet in 1990, and in the TMD, it jumped to 10,300 square feet from 9,000 square feet.

Although researchers observed a slight decline in the number of trees in the park, prickly pear and saguaros, as well as Brittlebush, a smaller perennial plant that favors warmer conditions, have greatly increased in number.

“There is some evidence that the long-term drought of the past 20 years is beginning to impact some species,” said Swann, “but the results also show how slowly desert plant communities change. Many plants that were present on the plots in 1990 are still there today.”

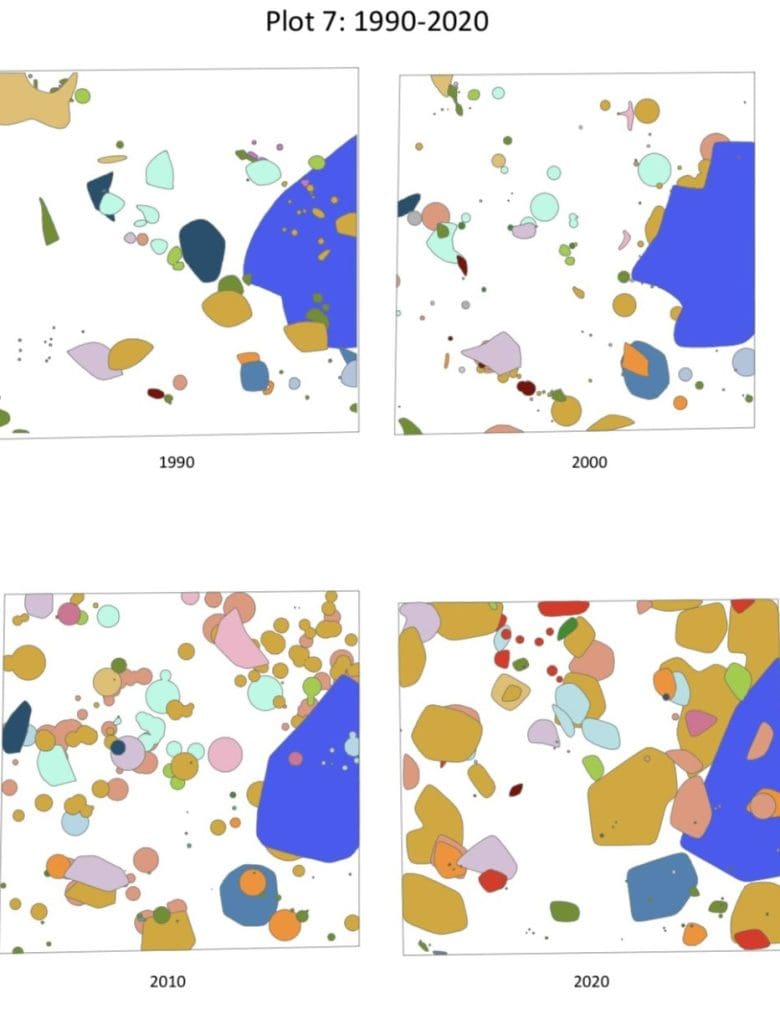

The saguaro surveys are taken on 45 plots, each approximately 10,000 square feet. Twenty plots are randomly located in the TMD, and 25 are located within saguaro habitat in the lower elevations of the RMD. Within these large plots are 1,100-square-foot subplots. During the surveys, the researchers record all plants on each subplot and map their cover area.

The 30 years of data suggest that long-term climate warming, suburban sprawl and random events, such as wildfire and above-normal precipitation, are significantly affecting growth patterns. All of the plants they mapped flourished after cattle grazing ended in the 1970s, and during wetter, cooler conditions throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. Since then, the park and desert Southwest have experienced extended long-term drought, punctuated by short wet periods.

Drier, warmer conditions have been favorable for prickly pear and cholla, but less so for shrubs. Researchers in 2010 discovered a surge in small subshrubs that resulted from heavy summer rains in 2006. Some individual plants were killed by a deep freeze in 2011, but the long-term effects, according to the researchers, appear to be relatively small.

“It’s a fascinating park if you’re a biologist,” said Swann. “It goes from low desert elevations, where it’s very hot and dry, to 9,000-foot elevations that are overspread with conifers. Being at the top of the Rincon Mountains is like being in Maine or Oregon.”

The research is taking place in the Sky Island region, isolated mountain ranges that are an extension of the Sierra Madre Mountains. The area contains a mix of dry desert and subtropical plants. A lot of these plants grow like saguaros, said Swann, and their reproduction and growth are tied to reliable summer rains.

While the general number of and cover for plants have ballooned in the park since the 1990s, there have been winners and losers among species. Among common trees, velvet mesquite and foothills palo verde have declined, while white-thorn acacia and wolfberry have prospered. Among shrubs, the density and cover for creosote, pelotazo or hoary abutilon, and jojoba have remained stable, while fairy duster and limber bush have bloomed.

Nearly all common subshrubs have expanded in range, except for triangle-leaf bursage, a common species in the TMD that has decreased slightly in cover and density. Brittlebush, which exploded in numbers in 2010 following heavy summer rains in 2006, decreased in number in both districts by 2020 but increased in cover.

“This project highlights the huge plant diversity that we can see in the low-elevation Sonoran Desert,” said Fule, the lead author of the report who did most of the field work, as well as the data management and mapmaking. “In only 1,100 square feet, it was common to find over 20 different species, and on several plots we found as many as 30 species.”

Among cacti and succulents, prickly pear stands out as a dominant plant, more than doubling in cover in the RMD since 1990. Pincushion cacti have doubled in the same period, while the barrel cactus has declined by more than half. From 1990 to 2020, the overall cover of three common cholla species increased mainly because of an eruption of jumping cholla.

Plant communities, however, aren’t shaped by just large-scale, long-term environmental change. Rare events, such as wildfires, freezes, windstorms, and droughts, can spur their growth or hasten their decline. Since 1990, the park’s plants have been met with three very wet winters, a summer of torrential rain in 2006, and a deep freeze in 2011 that defied the prolonged drought and historically high temperatures.

During that wet summer in 2006, subshrubs, such as Brittlebush, multiplied to such an extent that surveyors in 2010 had to modify their sampling methods to accurately map the plants that were by then 3- to 4-years-old. The freeze in 2011 was a sudden reversal of fortune for many of the cold-intolerant Brittlebush, which died off in significant numbers. Overall cover did expand, however, as they continued to mature.

Indigenous peoples drew sustenance from saguaros long before the cacti became a celebrated symbol of the Southwest. The Tohono O’odham, or Desert People, have lived in the Sonoran Desert for thousands of years. Their harvesting of the Saguaro fruit is a centuries-old practice that reaffirms their relationship with their traditional environment. They use the flowers, fruit, seeds, thorns, burls or boots, and ribs of the saguaro for food, ceremonies, fiber, manufacture and trade, and they use the fruit and seeds to make a ceremonial wine that is used in the Navai’t, and the Vikita, or harvest ceremony.

Saguaros are a master of survival and they reproduce for more than 100 years, but the species doesn’t produce a fresh crop every year. They like cool, wet conditions, and are especially resilient once they mature, but climate-induced drought over the long-term may affect their numbers in the park.

“Adult plants tend to survive and be much more resilient to drought than young plants,” said Swann. “Saguaros are a good case study of this. Once they reach a certain age when they can store water, it’s incredibly resilient to change and drought, whereas the new ones are decreasing in number. We’re not alarmed by this development, but we’re keeping an eye on it.”

The park’s evolving vegetation has also affected two species of deer in the park—white tail deer and mule deer, which like to eat saguaro flesh that hoards water. White tail deer tend to inhabit higher elevations and like to hide in the forest, while mule deer roam the grasslands and desert. Over the past 30 years, the researchers have seen a shift in behavior.

“In the 1970s, the white tail deer inhabited elevations at 5,000 to 6,000 feet and their presence in the desert was unusual,” said Swann. “Now they’ve moved into the desert where plants provide cover for them. Since mule deer can’t see as far, they’re uncomfortable with the plant cover.”

Swann called the Saguaro Census a “partnership of generations.” He said the team of researchers, which includes 500 volunteers, is “grateful” for the support from WNPA and the Friends of Saguaro National Park that is allowing them to continue the 80-year-old program.

“Saguaro National Park is particularly biologically diverse and has a rich scientific legacy that we feel responsible for continuing,” he said. “A lot of people who started the studies that I’m working on have been dead for a long time. Like them, I hope that I become a conduit for young people to continue these studies long after I’m gone.”