Fort Davis and the Trail to Civil Rights

Equality and Justice for All. Heavy words, aren’t they? Even more so when put together. From the American Revolution to the Civil War, African Americans were encouraged to fight for America but were not allowed to serve with benefits during peacetime. It wasn’t until 1866 with the formation of six all-Black regiments that would become the 9th and 10th US Cavalry regiments and the 24th and 25th US Infantry regiments, that African Americans could serve in the Regular Army.

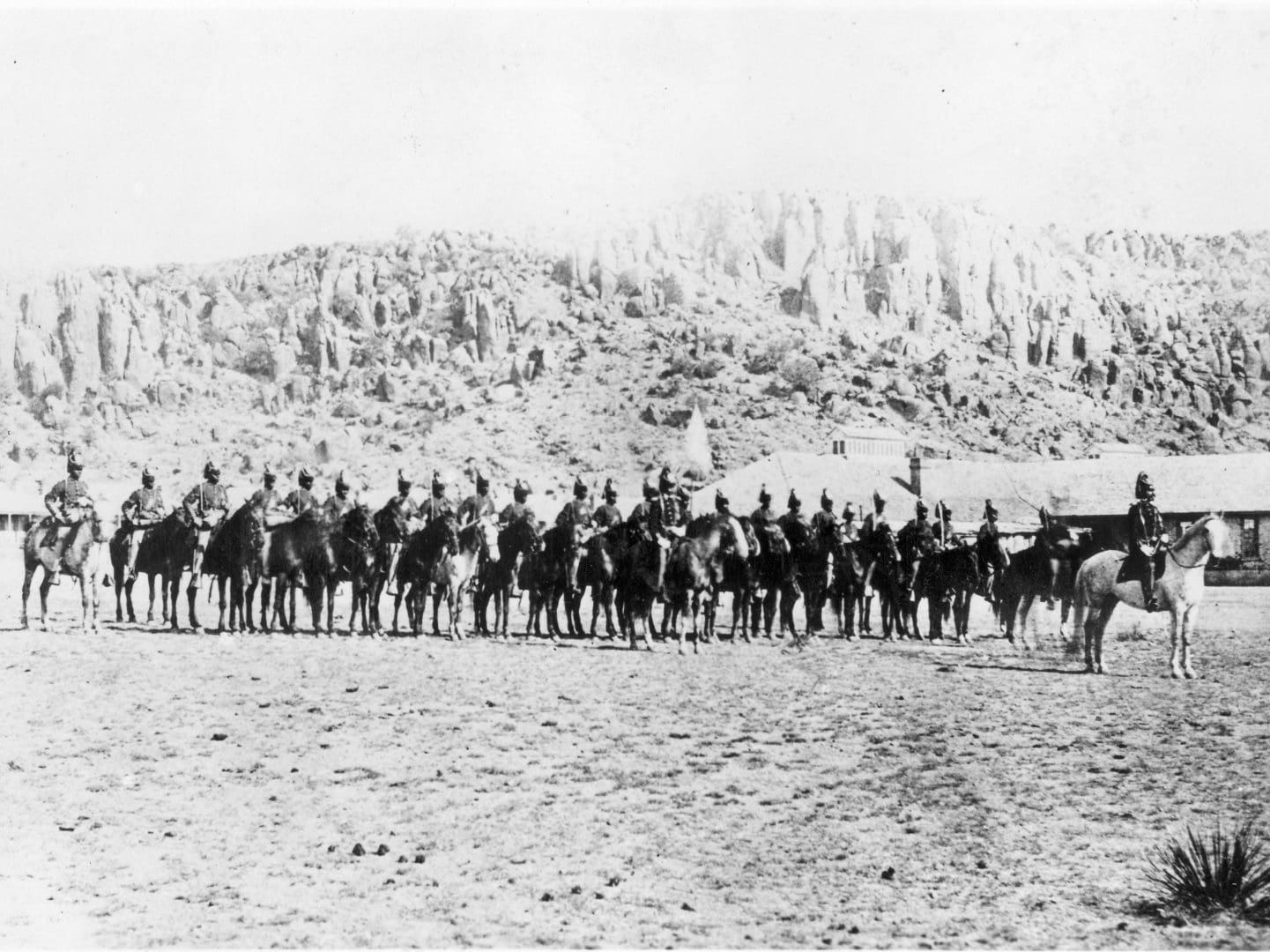

Troopers of the Ninth US Cavalry were the first “Buffalo Soldiers” to garrison Fort Davis. On July 1, 1867, Companies C, F, H, and I, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Merritt, officially reoccupied the post that had been abandoned since 1862. Troops from all four Buffalo Soldier regiments would serve at Fort Davis from 1867-1885, providing an invaluable service by repairing military telegraph lines, scouting, guarding water holes, escorting government wagon trains, survey parties, freight wagons, and mail coaches during the Indian Wars.

In addition to the many Black regulars who served at Fort Davis, the post also saw the first Black officer to graduate from West Point, Second Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper. While his time in the US Army would be cut short due to racial prejudice, his achievement of breaking barriers is not forgotten.

The US Army also served as a means for African American women to have a steady income as well as a sense of financial freedom. Women of color could serve as army laundresses and were a recognized part of the frontier army. They were given pay, were allotted rations, were given fuel and quarters, and were allowed medical care by the post surgeon. Laundresses were attached to a company and would follow that company from post to post at the expense of the US Army. Each company was permitted to have up to four laundresses, and not one laundress could do laundry for more than nineteen men. Often times, laundresses were the wives of enlisted men. Laundresses were paid by the soldiers at a rate set by the post council. At the pay table, laundresses received payment deducted from the soldiers’ pay. Charges varied from time period to time period, and from post to post, but generally they received about $1.00 per month per enlisted man and $3.00 to $4.00 for washing for officers. An industrious laundress could make $30.00 to $40.00 per month, or 2-3x more than an enlisted man.

Completed in Spring 2021, Fort Davis National Historic Site debuted a ten minute video “Fort Davis and the Trail to Civil Rights” addressing 400 years of African-American history from “auction block” slavery to “cartridge box” military service, and “voting box” citizenship to President Obama in the Oval Office.

Designed for 4th-8th grade students, these educational videos address our country’s culturally diverse history. This project was geared to promote NPS goals of Relevance, Diversity, and Inclusion (RDI) by facilitating and introducing connections between students from all backgrounds with park resources not only at Fort Davis National Historic Site, but other National Park Service units.

Next, curriculum will be developed to compliment the videos to enable us to reach out beyond our boundaries to youth across the country.

By: Chelsea Rios, Chief of Interpretation and Education and Sebastian Flores, Park Ranger/Historic Weapons Supervisor, Fort Davis National Historic Site