John Muir: A Passion for Nature

Equality and Justice for All. Heavy words, aren’t they? Even more so when put together. From the American Revolution to the Civil War, African Americans were encouraged to fight for America but were not allowed to serve with benefits during peacetime. It wasn’t until 1866 with the formation of six all-Black regiments that would become the 9th and 10th US Cavalry regiments and the 24th and 25th US Infantry regiments, that African Americans could serve in the Regular Army.

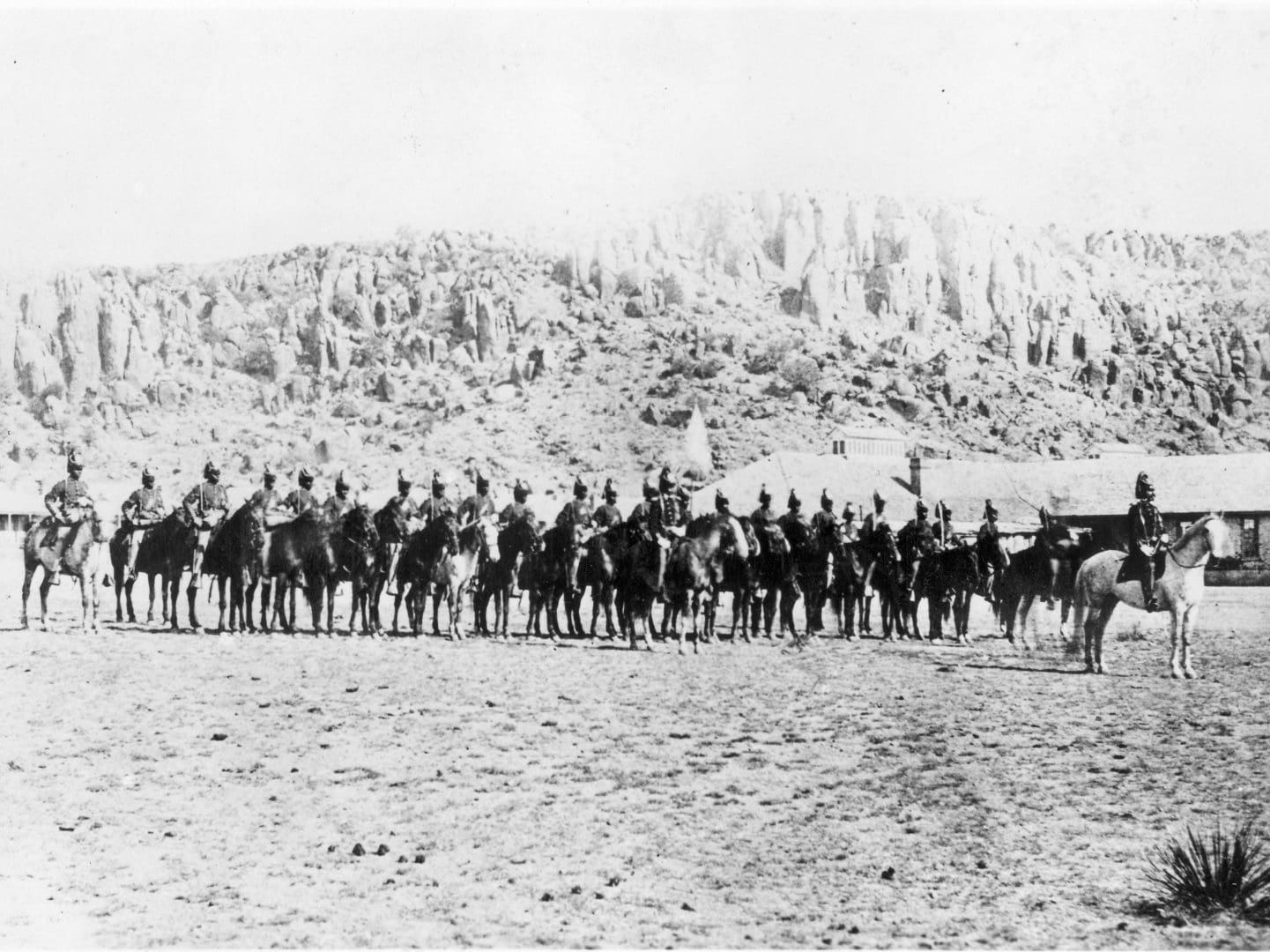

Troopers of the Ninth US Cavalry were the first “Buffalo Soldiers” to garrison Fort Davis. On July 1, 1867, Companies C, F, H, and I, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Merritt, officially reoccupied the post that had been abandoned since 1862. Troops from all four Buffalo Soldier regiments would serve at Fort Davis from 1867-1885, providing an invaluable service by repairing military telegraph lines, scouting, guarding water holes, escorting government wagon trains, survey parties, freight wagons, and mail coaches during the Indian Wars.

In addition to the many Black regulars who served at Fort Davis, the post also saw the first Black officer to graduate from West Point, Second Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper. While his time in the US Army would be cut short due to racial prejudice, his achievement of breaking barriers is not forgotten.

Completed in Spring 2021, Fort Davis National Historic Site debuted a ten minute video “Fort Davis and the Trail to Civil Rights” addressing 400 years of African-American history from “auction block” slavery to “cartridge box” military service, and “voting box” citizenship to President Obama in the Oval Office.

Designed for 4th-8th grade students, these educational videos address our country’s culturally diverse history. This project was geared to promote NPS goals of Relevance, Diversity, and Inclusion (RDI) by facilitating and introducing connections between students from all backgrounds with park resources not only at Fort Davis National Historic Site, but other National Park Service units.

Next, curriculum will be developed to compliment the videos to enable us to reach out beyond our boundaries to youth across the country.

Grieving their losses, the Strentzels yet again persevered and moved to a 20-acre plot in the beautiful Alhambra Valley near the town of Martinez, California. Dr. Strentzel used his Hungarian vineyard knowledge to begin experimenting with a wide variety of grapes, fruit and nut trees, as well as ornamental plantings. His small experiments soon grew into a lucrative fruit ranch of 26,000 acres, with labor provided by Chinese workers. Sadly, the son Johnnie died at 9 years old from diphtheria, and Dr. Strentzel reported, “For years, we were inconsolable.”

So, when a smart charming John Muir came to visit the Strentzels in Martinez, they were overjoyed to host him. Muir and Louie married in 1880 and had two daughters, Wanda and Helen. The family let Muir share the management and wealth of the ranch business, and with this influential position, he was able to catch the eye of politicians and business owners in his future advocacy for protecting wild spaces. If not for John Muir marrying into a pioneering, resilient, and wealthy family, he might have been just a poor rambling leaf-lover still wandering around Yosemite.

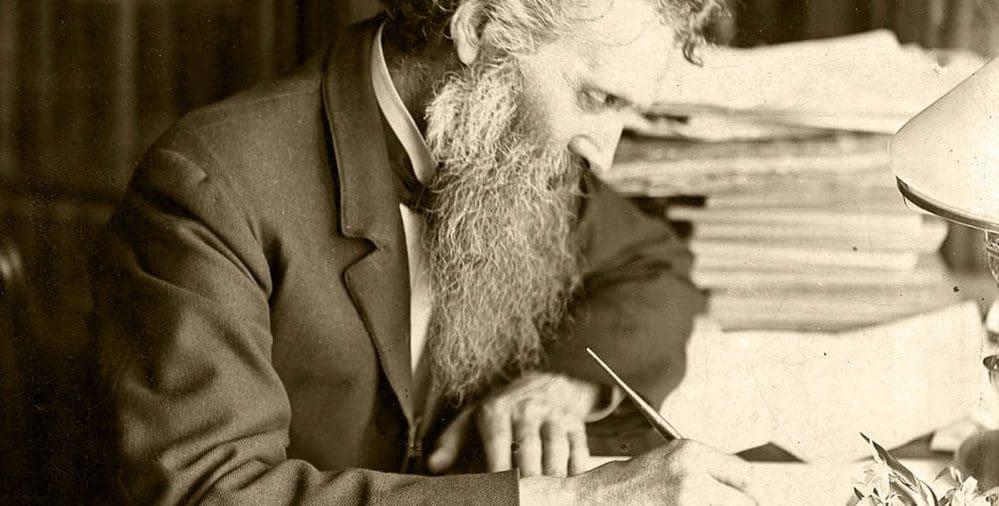

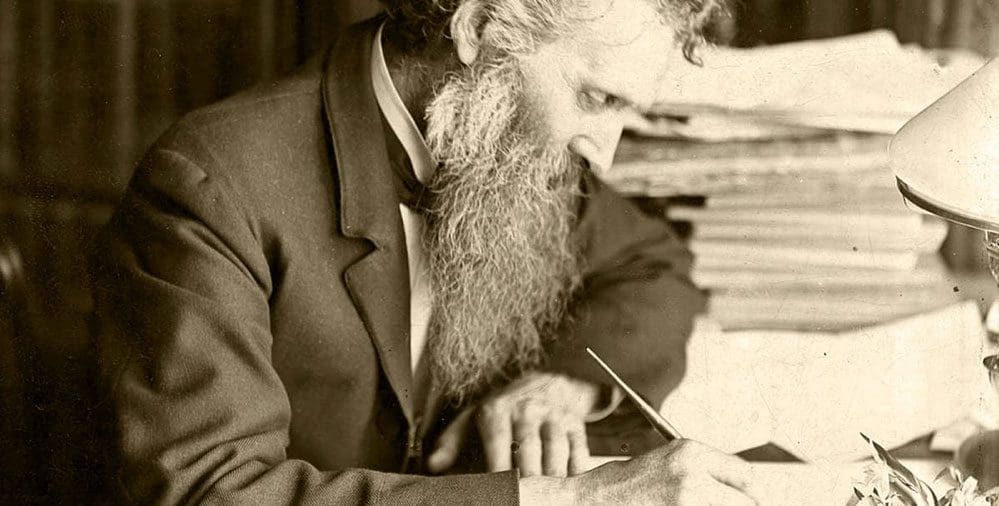

Muir’s passion for nature brought him to every continent except Antarctica. He experienced fantastic adventures – climbing a 100-foot tree in a thunderstorm, inching across a narrow ice bridge in Alaska, and spending a night in a blizzard on Mt. Shasta. Muir transformed his adventures into articles and books that sparked peoples’ interest in nature. Muir’s descriptions of glaciers and sequoias brought the beauty of nature to readers nationwide.

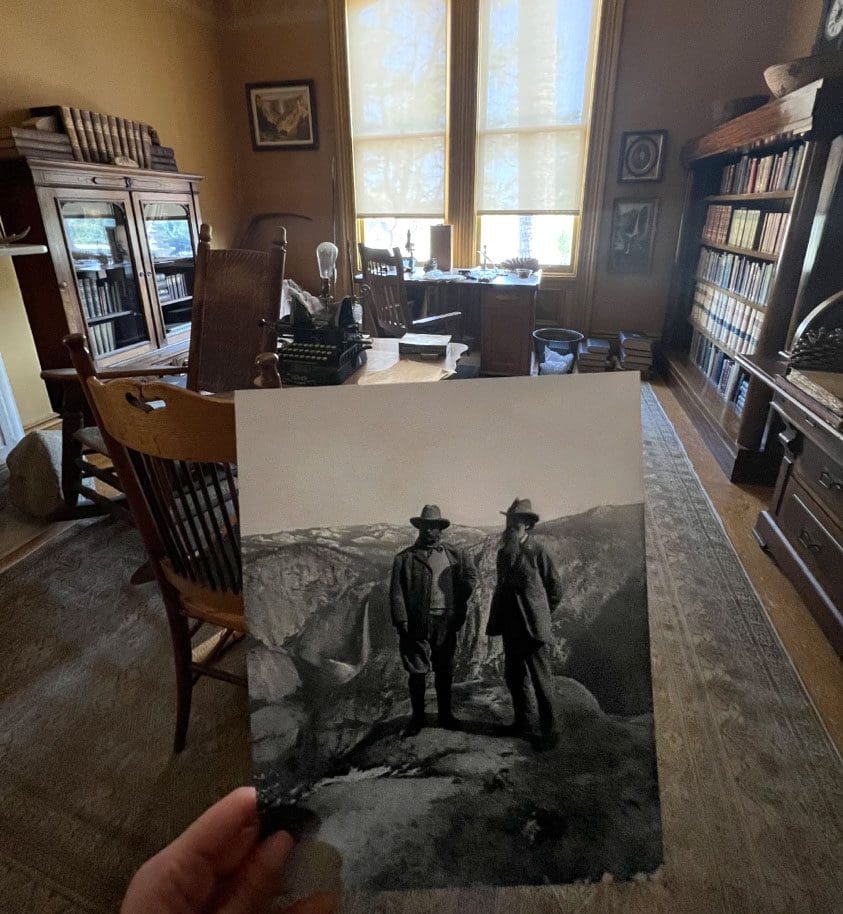

As increased settlement ended the western frontier in 1890, people began to worry about using resources wisely. Unchecked grazing, logging and tourism were damaging Yosemite. In response, friends and family encouraged Muir to write. He struggled with writing, calling it “like the life of a glacier; one eternal grind.” Yet he recognized the power of prose and worked tirelessly in his “Scribble Den,” his upstairs office in his Martinez home.

Wild spaces should be set aside for all to enjoy, Muir argued. He urged people to write politicians and “make their lives wretched until they do what is right by the woods.” His articles “The Treasures of Yosemite” and “Features of a Proposed Yosemite National Park” appeared in Century Magazine, which boasted more than one million readers. A month later, Congress designated Yosemite a national park.

Muir’s popular writings caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, who invited him to go camping in Yosemite in 1903. Roosevelt left behind reporters and his Secret Service agents for the company of two park rangers, an army packer, John Muir and the wild. They spent three days exploring meadows and waterfalls and three nights discussing conservation around campfires. One night, five inches of snow fell, and the president arose to white flakes on his blankets. Inspired by his trip with Muir, Roosevelt set aside more than 230 million acres of public land – an area bigger than the size of Texas – that included five national parks and 18 national monuments.

We all have legacies that will extend beyond our lifetime. Muir died on December 24, 1914 at age 76, just two years before the establishment of the National Park Service. The Service was created when the Organic Act was signed by President Woodrow Wilson on August 25, 1916. Even after Muir’s death, his journals and other writings provided material for many more influential books.

Thanks to Muir’s vision, you can now visit 423 National Park Service sites. Called “America’s Best Idea,” the United States’ unique system of protecting natural and cultural heritage spurred other countries to do the same. Muir’s writings and the places he fought to protect continue to inspire people worldwide to discover and connect with nature.

However, Muir’s conservation legacy is not without controversy. Two years ago, the Sierra Club made headlines with their July 2020 article “Pulling Down Our Monuments”, in which they expressed a desire to confront the racist perspectives held by some of their early leaders, as well as their “substantial role in perpetuating white supremacy”. Some excerpts from the article include: “[Muir] made derogatory comments about Black people and Indigenous peoples that drew on deeply harmful racist stereotypes, though his views evolved later in his life”. “As the most iconic figure in Sierra Club history, Muir’s words and actions carry an especially heavy weight. They continue to hurt and alienate Indigenous people and people of color.”

John Muir NHS welcomes the opportunity to discuss and bring to light these more troubling components of Muir’s work and legacy. We are dedicated to researching, interpreting, and sharing all aspects of Muir’s life and career – his family life in Martinez, California which afforded him wealth and privilege, the breadth and magnitude of his conservation work all over the world, as well as his negative views on people of color, and how those views – as well as the involvement of other conservation leaders with the eugenics movement – may have influenced the American conservation movement.

We have begun collaborating with Yosemite National Park and the John Muir Center at the University of the Pacific in conducting research on the more troubling aspects of Muir’s history, and are planning for a new exhibit at our site which will include online multimedia content exploring these topics, shedding light on the racism in some of Muir’s writings and the impacts they had on often underrepresented communities.

John Muir’s complex legacy – both the inspiring and the problematic – lives on at the John Muir National Historic Site and in our daily actions. There will always be a need for people to stand up and change their communities for the better, as well as an obligation to make sure that those changes are able to benefit even the most vulnerable in our society.

By: Ranger Ives Humphreys, Park Ranger, John Muir National Historic Site and Kelli English, Interpretation, Education and Outreach Division Manager, Rosie the Riveter / WWII Home Front National Historical Park, Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial, Eugene O’Neill National Historic Site, John Muir National Historic Site