Saguaro flowering is changing according to wildlife scientists

The mighty saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) is an icon of the American Southwest. Under a blazing sun, these majestic cacti can grow upwards of 50 feet if the conditions are right. A cursory glance with an untrained eye leaves one with the impression that these prickly giants are indestructible, however, Arizona scientists investigating flower blooming patterns over the last several years have observed their sensitivity to climate change-induced weather extremes.

Read on to learn more about how WNP-funded research engages citizen science in learning about and protecting these mighty giants.

Support your parks

Your national parks need your support more than ever. Since 1938, WNP has been a proud nonprofit partner of the National Park Service. With your support, we serve 72 national park sites across 12 Western states, helping visitors connect more deeply with nature, history, and each other. Your gift helps provide the essential programs, tools, and people that bring parks to life.

A keystone species

Saguaros are a keystone species, meaning that they provide essential resources such as flowers, fruit, and nesting space to over 100 different animals and insects that coexist in the Sonoran Desert. Buds appear each spring in late March or early April, relying on a delicate balance of sunlight, rainfall, and heat to encourage the first flowers to bloom. They open each evening for several weeks, closing before the warmest part of the afternoon. The key pollinators of these towering cacti are bats, like the Mexican Long-tongued (Choeronycteris mexicana) and the Lesser Long-nosed (Leptonycteris curasoae) and moths that are active at night; although honeybees and a variety of birds also pay visits during the earlier part of the day.

Following flowering season, bright red fleshy fruits, each containing up to 2000 small, black seeds, will appear. These fruits are quickly eaten by anything that can get its claws or paws in them, and the seeds are distributed far and wide, becoming the next generation of giants if conditions are accommodating.

When flowers bloom

Saguaro flowering is a carefully organized event; buds first appear on the east side of the crown (the name for the top of the main stem,) then bloom counterclockwise in succession on the north, west, and southern sides in a phenomenon that has not been documented in any other plant thus far.

In a project that launched in the western Tucson Mountain District of Saguaro National Park in 2017, co-principal investigators Don Swann and Theresa Foley set out to gain a better understanding of the flowering and fruiting behaviors of saguaros and how they might be changing in response to the environment.

Wildlife biologist Don Swann joined Saguaro National Park in 1993 and has been studying saguaros for the last 12 years. He became interested in phenology, or flowering behavior, after learning about the work of William D. Peachey, a research scientist and saguaro expert who has been studying the cacti in Saguaro East for decades.

“He’d been sending me his data, and it was fascinating, so I thought it might be great to have another site over here, near the Tucson Mountains,” Swann explained.

Peachey has been monitoring over 130 saguaros on a plot of land near Colossal Cave for the last 20 years, comparing bloom production with extreme weather events. These include very low rainfall as well as record-breaking temperatures – both high and low. We don’t typically think about freezes in the desert, but they do occur and wreak havoc on saguaros. The last major event occurred in 2011, with temperatures remaining below freezing for more than 36 hours. That year, Peachey saw virtually no blooms on his plot, which was mirrored in Saguaro West.

“I’ve also seen the same thing following very poor rains,” Swann explained. “For example, we’re expecting that this year is going to be quite different to last year where we had pretty good summer and winter rains.”

Saguaro blooms depend on winter rains. During the coolest season of the year, the cacti swell and store water, producing blooms several months later during the driest part of the year. These rains can be highly variable, but when a bad winter season is combined with weak summer monsoons, the saguaros are hardest hit.

“Looking at my data, I can’t say that it’s climate change, but I can say that the weather events exactly match the symptomology of climate change,” Peachey said.

Almost 40% of the years that Peachey has been monitoring blooms have experienced anomalous weather events. The resulting bloom production has been weak and there’s concern for what this might mean for the future of this slow-growing species.

Saguaros are vulnerable during their first few years of life before they’re able to store water in their stems. If they manage to survive, it’ll be another several decades before they produce their first flowers around age 35. Saguaros don’t start to put out arms until at least 60 or 70 years and can live upwards of 250 years.

This is one of the difficulties that scientists face when studying these slow-growers; a complete perspective of the lifecycle stretches well beyond the human lifespan. It is for this reason that Theresa Foley, an independent scientist studying saguaros alongside Swann, knew this project would be so important.

“There’s so much natural variability year to year,” said Foley. “That’s why we’re collecting all this data.”

The benefits of citizen science

Each day during the blooming season, Foley receives photographs from the citizen scientists who are out in the field using a 30-foot selfie stick to capture images of the saguaro crowns safely from the ground. She then manually counts the number of flowers on each of the saguaros.

“Maybe one day artificial intelligence could do it, but the human eye is actually better,” Foley said, on how the flower numbers are extracted from the photographs.

There are 55 saguaros in the study site in Saguaro West and between 80 and 100 photographs taken each day during the counting season. As the weather heats up, this often means early starts for the park staff and volunteers who help with the data collection.

“We do a lot of different types of citizen science at the park,” said Swann. Ranging from large groups of inexperienced volunteers to those who are specialists including interns and staff, this project wouldn’t have been possible without them.

Looking ahead

This year, the team at Saguaro West are experimenting with a new thermal camera to try to accurately determine the temperature at the crown, which is believed to be an important deciding factor – along with amount of precipitation and sunlight – in when and how much flowers bloom each season.

“We’re going to continue to experiment,” Swann said.

Some evidence suggests that saguaros are blooming earlier than in the past and if this is the case, this poses a threat to the pollinators that visit them.

Bats like the Lesser Long-nosed rely heavily on a pollination corridor of saguaros and other cacti in Arizona where they rear their young.

“They have to match the flower phenology when they’re ready to give birth because they’re stuck in one place for four to six weeks,” said wildlife biologist, Debbie Buecher.

Buecher, a bat expert, explained that climate change poses many questions in terms of how these and other key pollinators will adapt to changes in flower blooming.

“It’s hard to know how flexible they are,” Buecher said.

Lesser Long-nosed bats engage in a symbiotic relationship with saguaros. They benefit from an important food source from the flowers and fruit while also distributing seeds far and wide.

“They can forage 30 miles one way,” Buecher said, explaining that this benefits saguaros by ensuring that germlings aren’t having to compete with the parent plant after having fallen directly into the soil below, but rather stand a better chance of surviving elsewhere in the desert.

As well as temperature-induced changes to flower blooming, saguaros are under threat from buffelgrass. Native to Africa and Asia, buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare, Cenchrus ciliaris) was introduced to the United States in the early 20th century to feed livestock and reduce erosion in the arid lands. Hardy and drought-tolerant, buffelgrass has become a threat to saguaros that – like many species in the Sonoran Desert – are not adapted to survive wildfires.

“It provides fuel for fires between the desert plants and also competes with those plants for water,” Swann explained.

The park regularly removes large swathes of buffelgrass, but it’s a challenge keeping up with the high growth rate. Care must also be taken to prevent any damage to saguaros and other native plants in the process.

Recent evidence suggests that the Sonoran Desert is now facing a long-term drought that began in the 1990s. With last year the hottest on record in Tucson, scientists like Swann, Foley, and Peachey continue to be hard at work out in the field, seeing what’s next for the giants of the Southwest.

Guest Contributor Kat Kennedy, Doctoral Student at the University of Arizona

Explore more

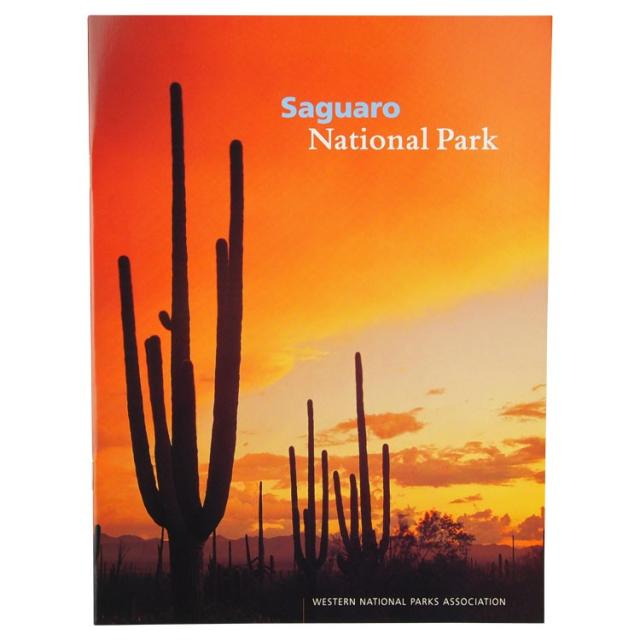

Saguaro National Park protects many wonders of the Sonoran Desert. Learn more or start planning your trip.

Three Days In Saguaro National Park

Saguaro National Park is small compared to Yellowstone or Death Valley national parks, and less than a quarter the size of nearby Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. But that doesn’t mean you should...

Exploring the Southwest's National Parks & Monuments

Discover diverse landscapes and rich Indigenous heritage of the Southwest on this two-week journey through three states.

Value Indigenous Voices: The Journey Toward a Deeper Understanding of the Southwest

In June of 2023, a WNPA-funded team of researches led by Deni Seymour, PhD, interviewed tribal and local community members to better understand the effects of the cultural collisions experienced in...

See the Astonishing Dark Skies Protected in Saguaro National Park

For thousands of years, people have been gazing at the stars through the cactus-studded, mountain-crested landscape of what is now known today as Saguaro National Park. Visitors to Saguaro after dark...