The InterTribal Buffalo Council Helps Tribes Welcome Bison Home

In the 1800s, the American bison, also known as the American buffalo, were hunted to near extinction. As part of a campaign to remove Native American tribes from their landscape, the US Army targeted the bison, a sacred animal to many Native tribes and a main food source. Without bison, it became easier to force Indigenous peoples onto reservations so that European Americans and the government could more easily profit from the land and control Indigenous defensive strategy. The army hired professional hunters who slaughtered bison by the hundreds of thousands, leaving most of the animal behind to decay. The images of this mass hunting looms over us, even today.

Yet, through the efforts of diverse conservation groups and Indigenous activists the bison are in resurgence, and efforts are underway to transfer these sacred animals to tribal stewardship, where they originally flourished. The InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC), formed in 1992, began as a collective of 19 tribes with a shared goal to reestablish healthy buffalo herds on tribal lands, an act of both cultural and natural healing. Today, the ITBC comprises 83 tribes across 20 states, and continues to grow in numbers and impact. “We work as a unified and unifying voice for the tribes,” said Troy Heinert, executive director of the council. “This program offers Native peoples a chance to reconnect with an important part of [their] culture,” Heinert continued. For Indigenous peoples, restoring the bison is a part of a healing process, completing and connecting a circle that involves many partnerships. With renewed stewardship, tribal members can build their herds and feel the wholeness of being in the presence of this sacred animal. The near eradication of the bison to control Native people requires a trust responsibility to begin to repair the harms done to Native peoples. The ITBC supports tribes as they rebuild herds, grow local economies, reintroduce healthy bison meat to Native diets, and many other means to build sovereignty and regain a part of what was taken from them.

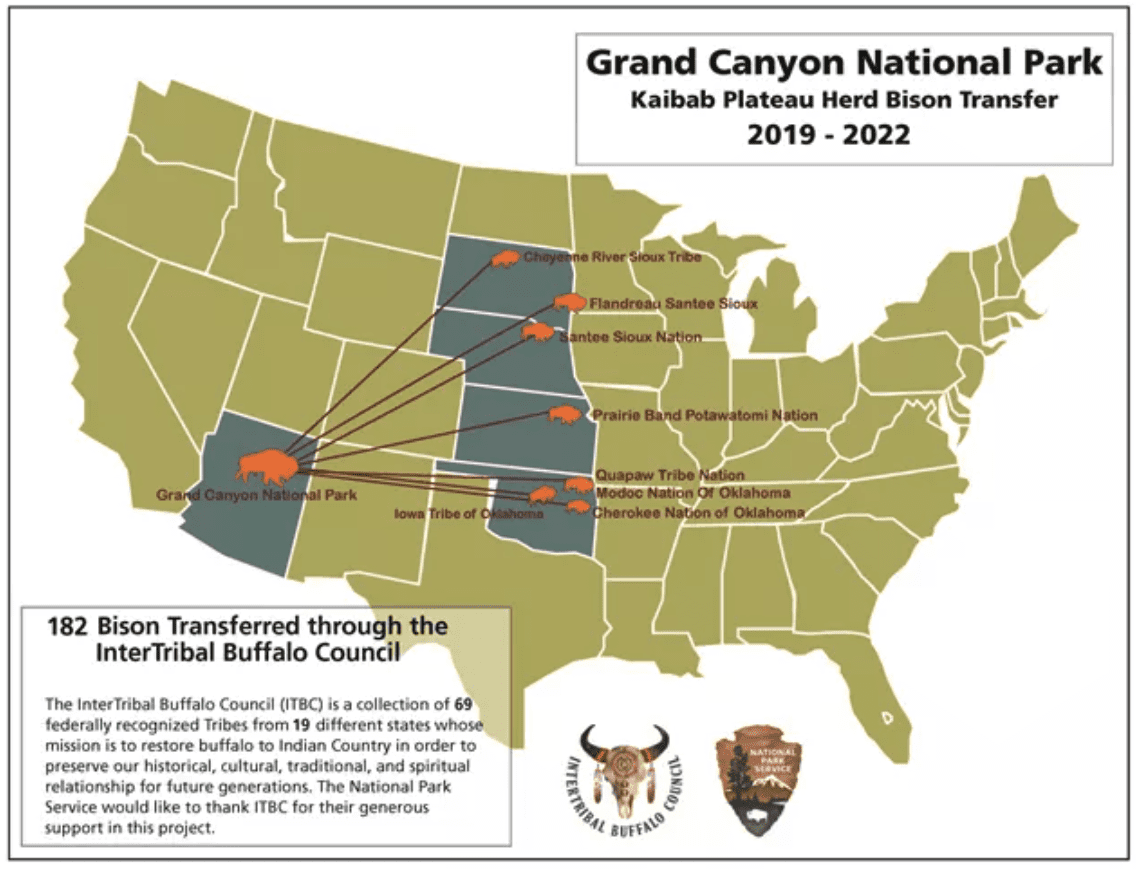

National parks such as Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon work with the ITBC to safely relocate bison from the parks, growing the Native herd in an effort to right past wrongs and prevent damage to the ecosystems that can happen when herds grow or graze, particularly in places that were not their principal natural habitat originally.

According to Miranda Terwilliger, wildlife biologist at Grand Canyon National Park, 182 bison have been safely transferred to tribal lands in cooperation with the ITBC. “The council determines which tribes get the bison,” she explained. Tribal autonomy is a key part of this relationship and the parks are here to support that, while taking care to manage the animals’ emotional stress levels and overall physical health. Arizona is on the edge of the bison’s historical range, according to Terwilliger. “You can tell the history of the continent through bison.” They are smart and sensitive animals whose movement patterns reflect an understanding of the dangers posed to them. While the herd on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim is a part of the original herd brought to the area by “Buffalo” Jones in the early 1900s, the animals also demonstrate unique genetic diversity, begging the question of how evolution has impacted their ability to survive climate change.

Through the collaboration of the National Park Service and other organizations, the ITBC successfully manages more than 20,000 bison that roam more than one million acres of tribal lands. Working with groups like the Native Farm Bill Coalition, the ITBC works to protect and bring legislative support for bison and Native agriculture, advocating for food sovereignty and regenerative farming. “All the money we raise goes directly to the tribes,” said Heinert. Support comes in all forms—letter-writing, social media amplification, outreach to local legislators.

By returning the bison to the peoples who hold them sacred, the land is also replenished, regaining much-needed biodiversity through the movement and grazing of the herd. With this replenishment comes the hope of future generations as they connect with the bison, who, in many tribes, represent strength, unity, and wholeness.

If you would like to learn more about the work of the InterTribal Buffalo Council and how you can support this important movement, follow the council on social media and check back in with WNPA for updates.

By: Julie Thompson